CCP Sheds Light on the History of Racial Justice Advocacy

25 June 2020

As the nation grapples with the disproportionate impact of police brutality and the COVID-19 pandemic on African American communities, the Colored Conventions Project (CCP) illuminates the relationship between historical and contemporary movements for racial justice.

The CCP provides primary-source documents and online exhibits related to the “Colored Conventions,” meetings held by African American activists and leaders from 1830 to the turn of the twentieth century. Hundreds of conventions took place throughout the United States, with attendees organizing around abolition, education, voting rights, and other issues of racial justice.

Jim Casey, Perkins Postdoctoral Fellow in the Council of the Humanities, explains that CCP emerged from a course taught by P. Gabrielle Foreman at the University of Delaware, where Casey was a graduate student. As a student sitting in on the course during the Occupy movement, Casey was intrigued by a reading Foreman assigned: a document from an 1859 Colored Convention.

“In our conversations about these documents, in our last major moment of activism bubbling over, we thought: ‘What if we looked at more of these documents?’,” Casey recalls.

They began to research the topic, Casey says, knowing that “the historiography of the Colored Conventions had been shaped by the racial hierarchies we inherited from the nineteenth century.” Whereas the Colored Conventions had often been presented as a small subsidiary of the abolitionist movement, they were actually a phenomenon of their own—a Black-led, Black-organized, and Black-attended activist movement demanding serious scholarly engagement.

To bring attention to these meetings, Casey and Foreman, along with a team of graduate students and UD librarians, started by digitizing minutes from several dozen conventions in spring 2012. As their team expanded to comprise additional graduate students, library staff, and faculty, CCP also began to expand its audience. It was not sufficient to digitize documents “and expect that to do the work for us,” Casey explains. Guided by the CCP’s principles, it was also essential to make the material "accessible to people who are not professional historians."

Over the years, CCP grew into a multi-faceted digital humanities and public history initiative, with committees on Community and Historic Church Outreach, Curriculum, Communications, and more. Douglass Day, a yearly crowd-sourced transcription event held at sites across the country, emerged from CCP, as well. This year, Casey organized the Princeton-area celebration alongside Princeton graduate students Julia Grummitt (History) and Elena M’Bouroukounda (Architecture), who served as University Administrative Fellows at the Center for Digital Humanities in 2019-20.

CCP has remained true to its scholarly goals. A volume of essays co-edited by Foreman and Casey, titled The Colored Convention Movement: Black Organizing in the Nineteenth Century, is forthcoming from UNC Press.

At the same time, the CCP team is considering “how the work of preserving these histories intersects with echoes of these histories now." On June 1, several CCP members, including Denise Burgher, Gabrielle Foreman, Kevin Winstead, along with Shirley Moody Turner of Penn State, co-convened “#CovidWhileBlack PA: A Digital Roundtable,” an online event featuring activists and leaders from Pennsylvania. A video of the roundtable is available via Periscope.

“Public health and voting rights are not just abstractly connected,” Casey explains. He adds that African American communities have historically suffered disproportionately during public health crises and have been subject to voter suppression and underrepresentation in the census. Advocacy around suffrage at the conventions lives on in attempts to combat voter suppression today.

Accordingly, CCP has added links to both voter registration and the 2020 Census on its website.

Given that CCP started by making us aware of the vital work of African American activists in the past, it is fitting that the project team is also using its platform to share resources promoting, as they put it, “a future where Black Lives Matter.”

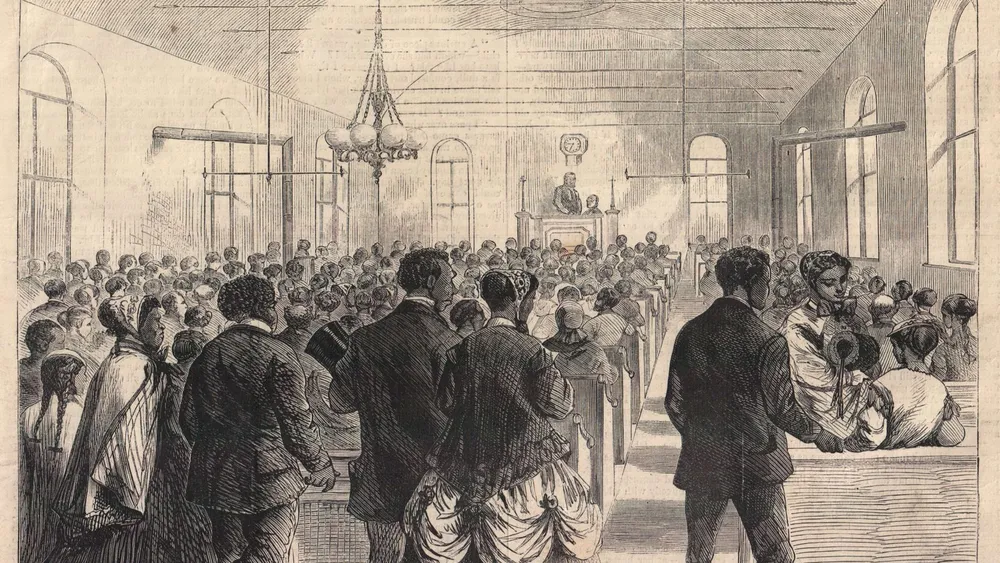

[Homepage image: courtesy Jim Casey]