Senior Thesis Prize winner developed a Python program to explore “secretive sentence structure” in Gothic fiction

2 October 2024

CDH Senior Thesis Prize winner Teddy Leane ’24 (English) told us about his project.

This spring, we were pleased to award the CDH Senior Thesis Prize to Teddy Leane ’24 (English). Teddy's project, “Unspeakable: Syntax and Secrecy in the Fin de Siècle Gothic,” was advised by Professor Susan Wolfson.

First, please give us a quick overview of your project. How would you describe it in three to four sentences?

The late-ninteenth-century Gothic story is often structured around an unnamed or unnameable secret. I was interested in the effect this has on the reader’s experience of the text and the structures in the language that produce this atmosphere of secrecy. For example, I noticed some authors leave out the noun subject, creating agentless sentences where who’s doing what is ambiguous. I looked at case studies of different types of evasive language I found in Victorian Gothic texts. I wrote code that uses computational linguistics methods to identify these secretive grammatical structures, so I could compare their frequency across texts and genres to see if this is a unique feature of the Gothic.

How did you develop your topic?

I was interested in moments where language “fails,” and in texts that circle around something they can’t seem to bring themselves to say. I had taken a class with Prof. Wolfson sophomore year where we discussed the passage on Death from Paradise Lost (“The other shape, / If shape it might be call'd that shape had none…”). Burke praised it as a great moment of sublime mystery, and Johnson hated it because it “shock[s] the mind by ascribing effects to nonentity.” It’s a strange description because it doesn’t tell you anything – it keeps contradicting itself, so you come away knowing even less than you did before. That intrigued me and got me thinking about other texts I’d seen that in. I had the opportunity to get a head start on my thesis over the summer with the Bread Loaf School of English, where I had some great conversations with classmates and Tamsen Wolff that helped me hone in on that interest and realize there was a thesis in there.

Tell us about the digital element of the thesis.

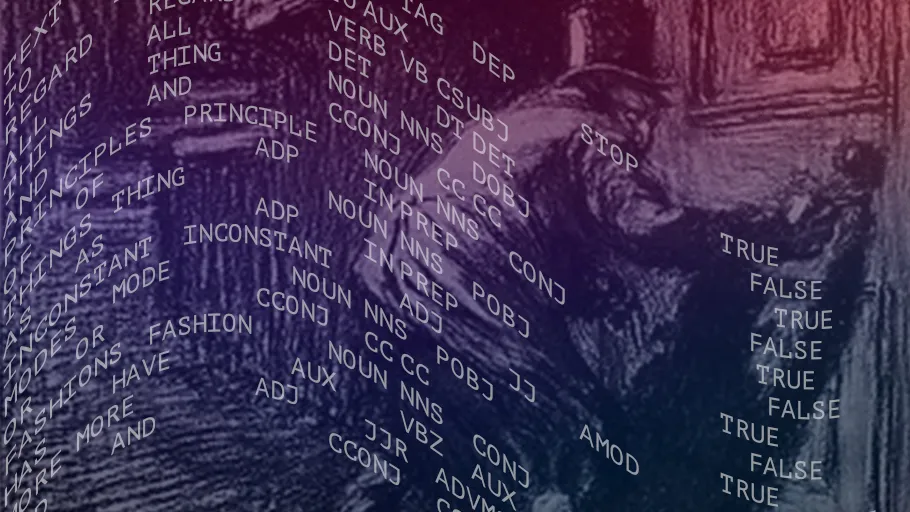

I wrote a Python program (I call it the “Obscure Structure Detector”) that uses the NLTK, SpaCy, and Stanza natural language processing packages to sift through a corpus of novels, plays, and short stories, finding the seven different kinds of secretive sentence structure I identified in the traditional humanities part of my thesis. It keeps a tally of each kind of secretive sentence and points me to where they occur in the texts. I had help from some great CDH staff, including Grant Wythoff and Laure Thompson, who directed me to SpaCy and Stanza.

How did you get the idea to include a digital component, and how did you learn the skills to implement it?

I took a lot of programming classes for the COS certificate, including “Introduction to Machine Translation” (TRA301/COS401/LIN405), which gave me a crash course in NLP that ended up being very useful. Linguistics also came in handy as a way to bridge computational and literary ways of thinking about human language.

I was interested in a big-picture view of the whole Gothic genre that also zeroed in on its syntax. I realized it required very close reading of a much larger number of texts than I could reasonably fit into one year. If I wrote code to do a preliminary sweep of the corpus for me and find occurrences of the grammatical structures I was interested in, I could focus my attention where it counted.

What is something you learned from the digital component of your project that you wouldn’t have learned otherwise?

I think it’s given me a much clearer picture of the strengths and limitations of digital humanities in literary study. Computational methods can be a powerful tool for focusing and multiplying the abilities of a human reader, providing more data that can expand the reach of an investigation and lead to entirely new kinds of insights. At the same time, I believe in the importance of the human in the humanities – I think the most difficult and valuable work will always lie not in running the numbers on texts to produce more texts and more data, but in the uniquely human work of interpreting these materials. Rather than destroying or replacing the human reader, our increasingly information-inundated age will require us to become skilled readers of many kinds of texts.

What’s next for you? Any connections between your thesis and your post-Princeton plans?

I’m excited to start a PhD in English this fall at Cornell, where I hope to continue working at the intersection of 19th-century literature and 21st-century technology.

Congratulations are also due to our CDH Senior Thesis Prize Honorable Mentions, Desi DeVaul ’24 (Classics) and Addele Hargenrader ’24 (ORFE).