DH at Princeton and Beyond: An Interview with Kent Cao *19

20 September 2022

Kent is a Princeton Ph.D. alum in Art and Archaeology who is now an assistant professor of art and archaeology at Duke Kunshan University and Duke University.

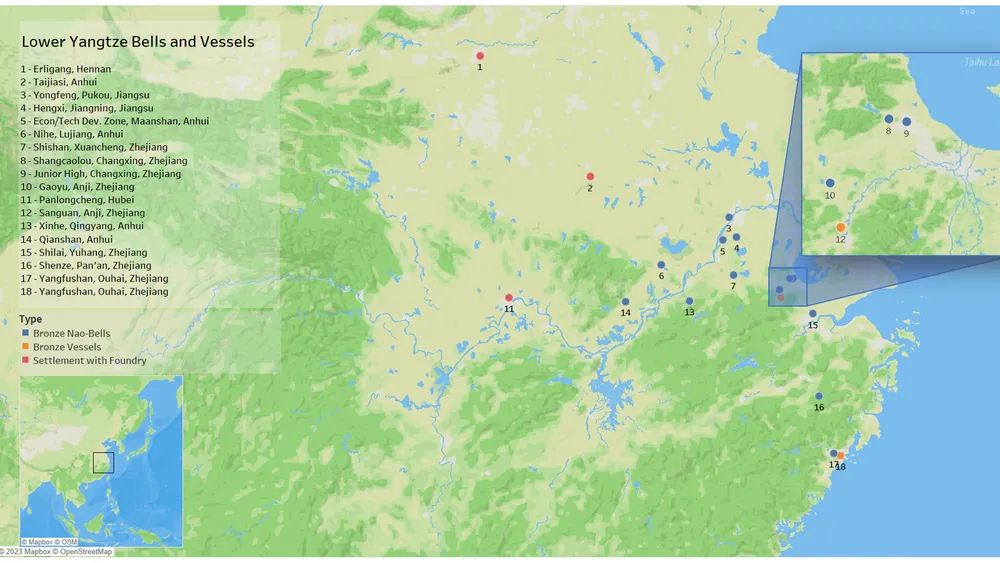

Updated May 23, 2023: Kent and collaborators have recently created an interactive map showing the locations of bronze bells and vessels found in the lower Yangtze region. Figure 2 has been updated accordingly.

We are excited to feature the work of Kent Cao *19, a Princeton Ph.D. alum in Art and Archaeology who is now an assistant professor of art and archaeology at Duke Kunshan University and Duke University, where he specializes in the art and archaeology of early China with a broad interest in the cultural interconnections within Eurasia.

When Kent was a graduate student, the Center for Digital Humanities supported his project, “Geography and Materiality: Digital Database for Bronze Art and Archaeology in South China,” with a seed grant. The project focused on indigenous bronze art and archaeology in south China (fifteenth to ninth century BCE) and created a new interpretative model for a database on bronze stray finds from the Yangtze region.

This interview with Kent highlights his CDH seed grant project, as well as how he has incorporated digital humanities into his research beyond his time at Princeton.

What were the origins of your seed grant project?

I knew that I needed to go through quite a bit of excavation reports and archaeological publications, and, on top of that, manage a large set of data for my dissertation. My primary research focus is the Bronze Age in the Yangtze River valley, South China (c. 1400 to 900 BCE). Often stumbled upon by local farmers by chance, these Yangtze bronzes (Figure 1) were buried individually on the hilltop or riverbank without other accompanying objects or clear archaeological context. So the idea occurred to me—why don’t I create a database that would make future work easier for myself and other scholars? As I started writing my dissertation, I gradually assembled a long Excel sheet documenting this vast discursive body of bronze artworks. The seed grant from the Princeton Center for Digital Humanities connected me with Meg Hicks (formerly at the CDH) and William Guthe (Research Computing), who helped me build a new interpretative model by cartographically integrating bronze photographs, rubbings, 3D models, and radiographs. Here is an early-stage outcome of the project, which will appear in my article on southern bells (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Bronze nao-bell, Shangcaolou, Changxin, Zhejiang, South China (c. 1200-1000 BCE), Zhejiang Provincial Museum.

Figure 2 Nao-bells and related bronze vessels, lower Yangtze region (c. 1300-900 BCE). An interactive version of the map is also available.

When did your interest in digital humanities begin?

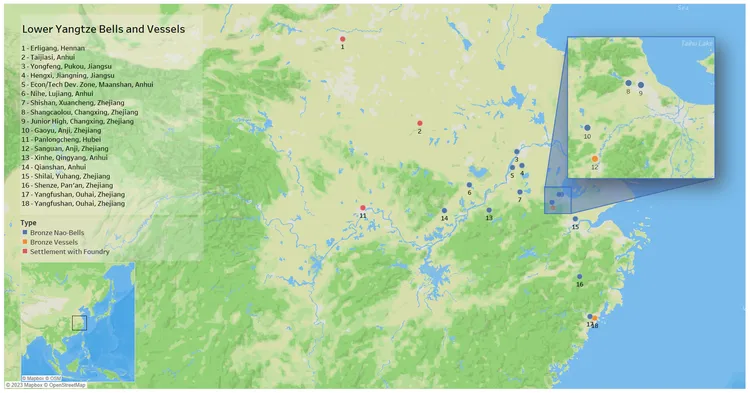

Back when I was an undergraduate, I saw a radiograph (Figure 3) of a Chinese double-ram zun 尊 ritual bronze vessel (Figure 4) in the British Museum. I was immediately intrigued. The dark dots in the radiograph are the bronze spacers used to keep the gap between the inner clay core and the outer clay molds. The molten bronze will then flow through the gap to form the vessel itself. It was eye-opening to see the synergy of art history, archaeology, and science in revealing a hidden layer of knowledge otherwise inaccessible to the naked eye.

Figure 3 Side view radiograph, Double-ram zun 尊 wine-vessel, the British Museum (1936, 1118.1)

Figure 4 Double-ram zun 尊 wine-vessel, the British Museum (1936, 1118.1).

How did your interest in digital humanities fit in with your grad school career?

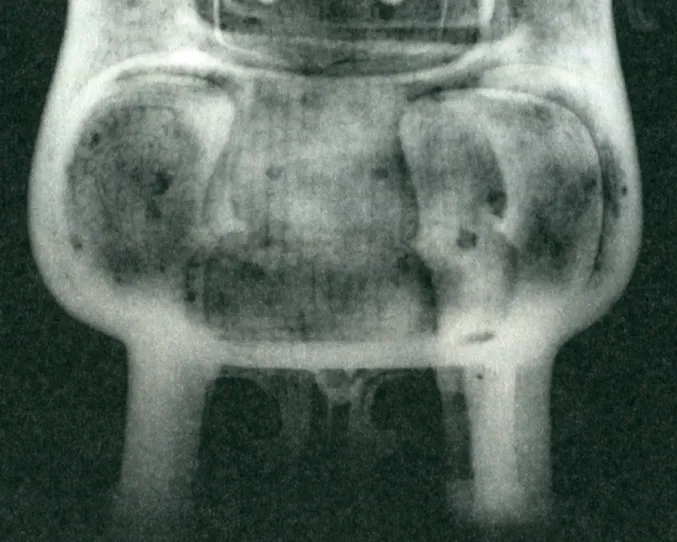

The interest in digital humanities drew me to different projects during my PhD years at Princeton. I was particularly excited about Ancient Art and the Higgs Boson: Non-destructive Muon Imaging, co-sponsored by the Department of Physics, the Department of Art and Archaeology, and the Princeton University Art Museum. This teamwork aimed to examine the application of the high-mass Muon particle imaging (Figure 5, modeling done by our physicist collaborators) in the high-density ancient artworks (Figure 6). The technical base of this project is rooted in the works by the particle accelerator laboratories (e.g. CERN and Fermilab), which have been using muon beams to explore the Higgs boson. Higgs boson is a fundamental particle in particle physics theory. Other elementary particles, including electrons and quarks, gain mass from the Higgs field.

Figure 5 (left) 3D reconstruction of a test object using VisIt, taken with 3 GeV muons. The object consists of 5 concentric spheres, with thickness 3, 9, 15, 21, and 30 mm, respectively, and 10 mm of water between different metallic layers. Each metallic layer consists of lead, copper, and iron of equal thickness. (Right) Cross-section view of the test object, and the muon absorption along a radial line. For the outer layers, we can identify three distinct materials indicated by the color in the cross-section, and the steps in the line plot. Burkhant Surerfu and Christopher Tully, High Resolution Muon Computed Tomography at Neutrino Beam Facilities, 2016 JINST 11 P02015. arXiv:1501.07238v1.

Figure 6 Gilt bronze figural lamp, mid-Warring States to early Western Han period (4th to 2nd century BCE), Princeton University Art Museum, 2003-29, Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund.

Has your project developed since grad school?

After graduating from Princeton, I have continued to add the latest excavation results to the database. I am also working with digital humanities specialists to expand the database by including relevant bronzes in various museum collections. My ultimate goal is to make this unified searchable system accessible to the public. I recently co-purchased a XRF scanner with my colleagues in Physics. This device can analyze the surface alloy compositions, which will supply a new group of technical data to the bronze studies.

Do you have future plans for using digital humanities in your research or teaching?

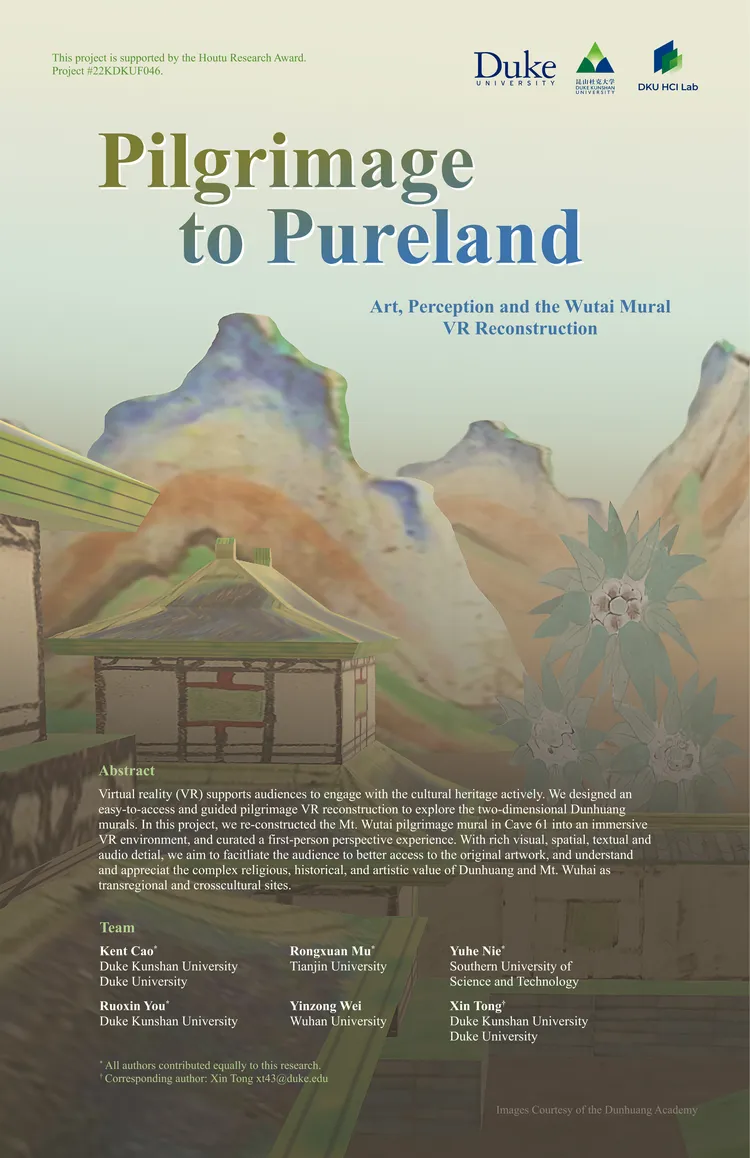

I’m currently teaming up with professors in Computer Science and Chinese Literature, and three student researchers to work on the virtual reality reconstruction of the Mt. Wutai mural in Cave 61, Mogao Caves, Dunhuang (Figure 7). We’ve been asking ourselves how to innovate the viewing experience of a two-dimensional mural painting. So in this project we explore the first-person perspective spatial perception in an immersive human-machine interface. In addition, I’m working with colleagues in Materials Science and Electrical Engineering on a project to investigate the interrelations between object form, metallic strength, and alloy compositions of ancient bronzes through computational simulations.

Figure 7 Conference Poster for Pilgrimage to Pureland: Art, Perception and the Wutai Mural VR Reconstruction.

What advice do you have for grad students interested in incorporating digital humanities in their research projects?

The academe is now increasingly interdisciplinary. Often it is not enough to be an expert in one narrow field. Humanists do not need to be programmers or engineers. But it is a crucial skill to learn how to propose a meaningful project, and how to collaborate with people outside your field. Princeton is fortunate to have a dedicated Center for Digital Humanities. I’m grateful to the Center’s seed grant, which truly planted a seed in my research and opened many doors. I would encourage everyone to think out of the box, do not be afraid to step into the unknown, and explore these digital humanities opportunities on campus.

Note: Although the CDH no longer offers seed grants, we continue to offer a variety of opportunities for graduate students, including Graduate Fellowships, Data Fellowships, and more.