Grassroots minstrelsy and the archive

15 September 2015

When I tell people I’m writing my dissertation on 20th century amateur minstrel shows in the United States, I am typically met with one of two reactions: shock that these performances occurred with such frequency (and well into the 1960s at that), or confusion about what a minstrel show actually is (many people have never heard of minstrelsy at all). When I tell them I attended an instance of staged minstrelsy in Tunbridge, Vermont last March (2015), utter bewilderment ensues.

Unlike the national memory of minstrel shows, remnants of what was once America’s most popular form of entertainment can be seen anytime one strolls down the grocery aisle or hears the catchy tune of the ice cream truck . What fascinates me is how these products of minstrelsy have become divorced from the source, especially when communities all across America were regularly holding amateur shows as local fundraisers just a few generations ago.

The production of minstrel shows by everyday Americans — which often featured not only blackface but drag — is a phenomenon I am calling grassroots minstrelsy. It was practiced by groups as disparate as Atlanta Western Union employees (1922), Los Angeles Athletic Club members (1942), and even U.S. Congressional spouses (1963). But despite its quotidian nature, grassroots minstrelsy’s material traces have been lost in virtue of their ephemerality. Because of this archival gap, very little work has been done to probe the communities that ritualistically staged these masquerades of race and gender.

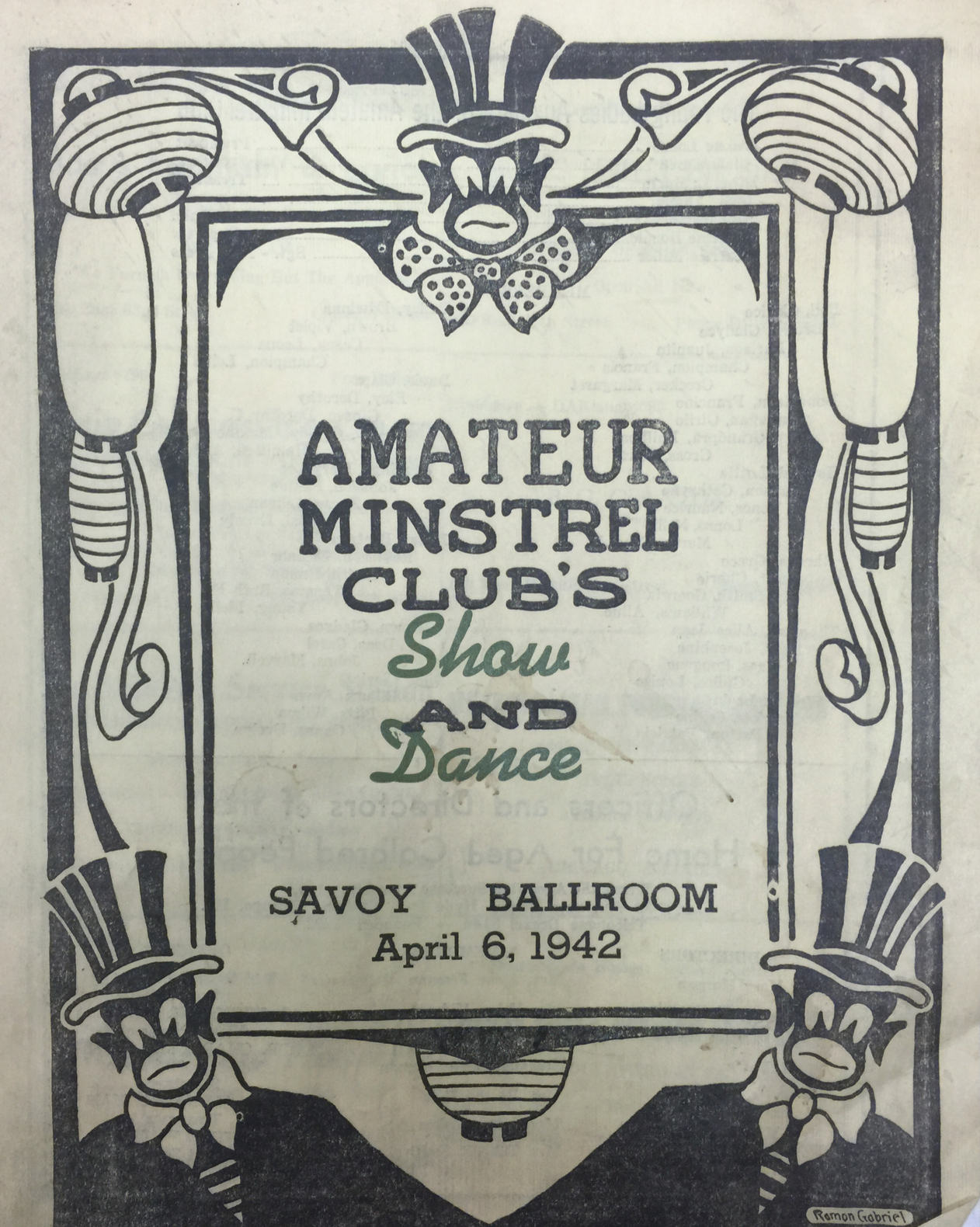

Grassroots Minstrelsy in Bronzeville — which studies the community of elite black Chicagoans who enacted annual minstrel shows Easter Monday night from 1897 to 1952 — began with the creation of an archive. Tracing the 50+ year history of South Side Chicago’s Amateur Minstrel Club included digital methods like scraping data from newspaper archives for information about the shows, census records for demographics about their performers, and sheet music collections for lyrics performers crooned on stage. But it also included analog methods like visiting vast repositories of Bronzeville history housed at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection at the Chicago Public Library.

One of the most incredible finds made during this archival journey was a small stash of programs printed for these Easter season performances. Of course the material inside each booklet contains a treasure trove of information about the very shows I had been meticulously reconstructing through newspaper reviews and advertisements. However, what was especially intriguing was just how much of a similarity the 1920 program bore to the 2015 Vermont production.

Though hard to show through static images, these programs felt the same in my hand. They were same in size, the covers identical in color, and each boasted a rich supply of local businesses supporting the shows’ charitable purposes. Despite being created in two vastly different local communities almost a century apart, both minstrel programs announced their ritualized recurrence and listed local community members as interlocutor and endmen. They could have easily been made by the same printers and designed by the same club member — different issues of a serial publication.

Not only does this comparison help me think about grassroots minstrelsy as a connected phenomena — as opposed to a series of isolated events — this archival anecdote also reminds me of the physical objects behind my digital project, materials that can often become abstracted and obscured when transformed into data. As I build the database architecture for my project and the user interface for visualizing the data it contains, returning to such archival discoveries helps me to contextualize the massive collection of fielded data with which I am working.