Shakespeare and Company Project Publishes Updated Datasets

On Monday, the Shakespeare and Company Project team reached an important milestone: we published updated data exports.

The Project illuminates the Lost Generation and life in interwar Paris by providing tools to explore material from the Sylvia Beach Papers, which are held in Special Collections at Princeton University Library. Beach owned Shakespeare and Company, an iconic bookshop and lending library that counted among its members James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, and many other prominent writers and intellectuals.

Three version 1.1 exports are now available to download on the Project : the first provides information about the members of Shakespeare and Company; the second centers on the books and periodicals that circulated at the lending library; and the third focuses on what the Project team calls “events,” a category that includes both membership activities (subscriptions, renewals, reimbursements) and book activities (borrows, purchases).

The version 1.1 exports comprise both additions and corrections to the 1.0 data exports, released in July.

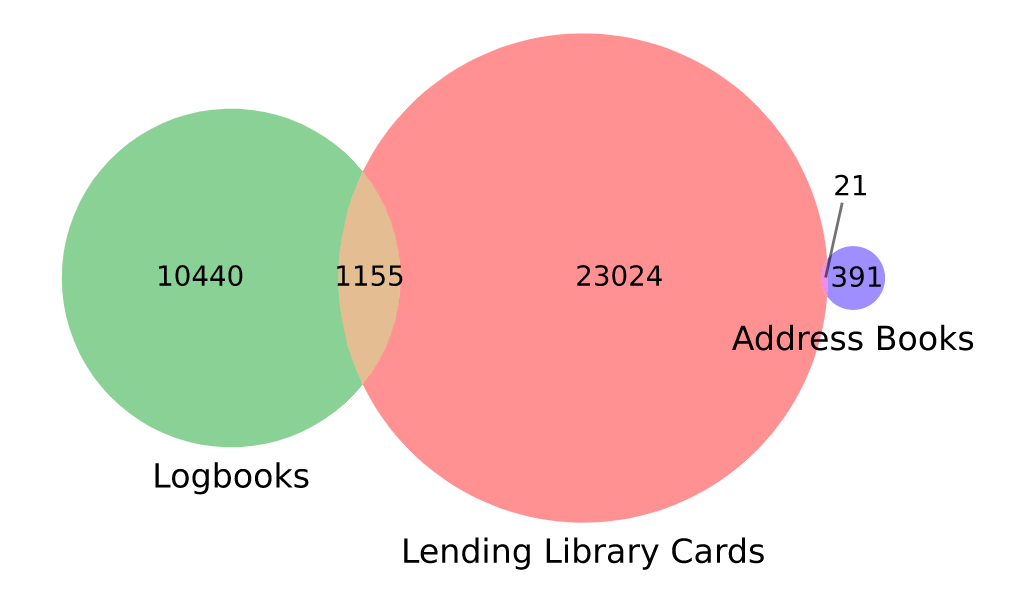

Additions to the data exports include information from all three Project sources : lending library cards, logbooks, and address books. The members dataset now features 859 new addresses from Beach’s address books, and the events dataset includes 1290 additional events. Whereas membership events in version 1.0 came almost entirely from Beach’s logbooks, version 1.1 includes membership events from the lending library cards, as well.

Researchers will also see two new fields in the updated exports: the duration of borrowing events in days, where available, and the source of every subscription and borrowing event (lending library cards, logbooks, address books). The events dataset also indicates if an event appears in multiple sources, and, if so, what those sources are.

In addition, over the months, members of the Project team discovered small mistakes in the data, including inaccurate publication dates for books and borrowing dates for events. Although many of these adjustments are small, they reflect hours of painstaking labor on the part of team members and are critical to providing accurate information to users.

Other corrections required more focused research. For instance, a recent thread from the Project Twitter account ( @ShakesCoProject ) details how senior researcher Ian Davis discovered that a lending library member named Jean Genet was not in fact the French writer of the same name, as we had previously thought. As Davis discovered, the writer Jean Genet was in La Santé Prison on the day the member returned a book to Shakespeare and Company.

Furthermore, when researchers learned two accounts belonged to the same person, they “merged” them into one account ( read our criteria for merging members ). Researchers also deleted mistaken records. As a result, the volume 1.1 member dataset shows 5601 members, whereas the version 1.0 data showed 5726.

A more comprehensive account of the exports can be found in the readme.

The new datasets will facilitate research that enriches our understanding of Beach’s world, intellectual life in interwar Paris, and modernism.

As someone with research interests in the 1800s, I hope to look closely at the nineteenth-century books that circulated at the lending library. What might attention to the reading habits of the community of Shakespeare and Company teach us about the reception of nineteenth-century literature in the twentieth century?

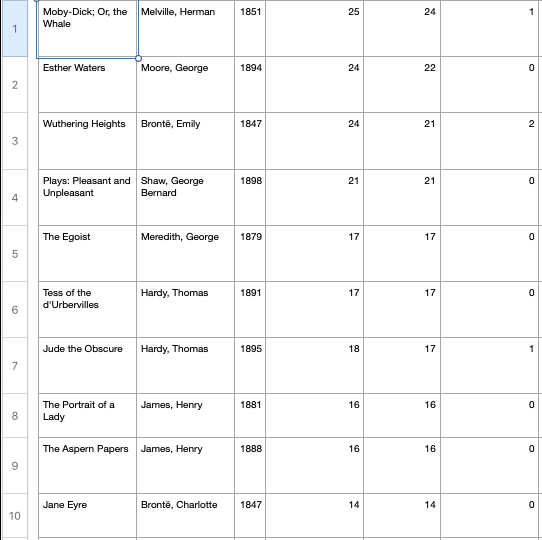

By sorting column K (books) in the books export, I learn 597 books published from 1800 to 1899 circulated at the lending library. By sorting those 597 books by “borrow_count,” I can begin to gauge their popularity.

The most borrowed overall? An American novel: Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), with 24 borrows. (For comparison, James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), with 56 borrows, tops the list of most borrowed books overall.) In a tie for second are two British novels: Emily Brontë’s still popular Wuthering Heights (1847) and George Moore’s (now) less famous Esther Waters (1894), both with 24 borrows. The latter, which chronicles the struggles of a single mother in Victorian England, should be read more often today!

In contrast, works by some of the best known nineteenth-century writers spent a lot of time on Shakespeare and Company’s shelves. Jane Austen’s and George Eliot’s most frequently borrowed books come in at number 18 ( Pride and Prejudice ) and 30 ( The Mill on the Floss ), respectively. Charles Dickens does not appear until number 38; his Great Expectations (1861) was borrowed only ten times.

Notably, Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918), which features not-always-admiring takes on Victorian heroes like Thomas Arnold and Florence Nightingale, boasts 18 borrows! France Emma Raphaël, one of Shakespeare and Company’s most active members, was the only individual to borrow both Great Expectations and Eminent Victorians.

What does this all mean?

I hope I can tell you someday. But this, reader, is a only a blogpost, written on a Sunday afternoon.

To make your own discoveries, head to the Shakespeare and Company Project data exports page. And stay tuned for the Project ’s upcoming collaborations with the Journal of Cultural Analytics and Modernism/modernity, which will feature essays using the updated data!