Combining Interests in Problem-Solving and Creativity

10 July 2023

An interview with AnneMarie Caballero ’23 (Computer Science), winner of the 2023 CDH Senior Thesis Prize

AnneMarie Caballero ’23 (Computer Science) received this year’s CDH Senior Thesis Prize for her project, “Gendered Topics: Boyhood and Girlhood in a Century of (Cotsen) Children’s Literature.” The award recognizes outstanding work which engages with or contributes to the field of digital humanities.

I interviewed AnneMarie about her award-winning project, her interest in digital humanities, and how she was able to combine two subjects she loves—Computer Science and English—through her senior thesis.

Tell me about your project.

My thesis, “Gendered Topics: Boyhood and Girlhood in a Century of (Cotsen) Children’s Literature,” examined a hundred years of children’s literature (from 1800–1900).

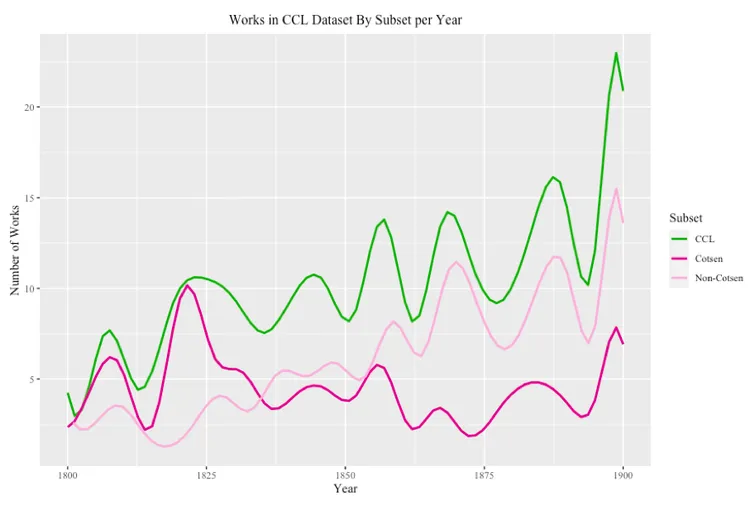

The first part of the project was curating a dataset of children’s literature. Unfortunately, no existing dataset fulfilled the project requirements: they either did not contain enough works or contained works from the wrong time period. As such, I used the nineteenth-century catalogue of the Cotsen Children’s Library, a special collection at Princeton, as a guide to create my own dataset: the Cotsen Children’s Literature (CCL) dataset. I chose the nineteenth century both because it was in the public domain, allowing unrestricted academic access, and because it was a time of great change in children’s literature—for instance, it includes much of the so-called Golden Age. The Cotsen Children’s Library also allowed me to look at a diverse set of works—novels, anthologies, magazines, short stories, and even creative non-fiction.

Smoothed trend line of the number of works in the CCL dataset per year, and in its two subsets, works contained in Cotsen (Cotsen) and works not in Cotsen (Non-Cotsen).

The second part of my project was using this dataset to answer questions about nineteenth-century children’s literature. While I originally hoped to explore several questions, I quickly realized that was too ambitious even for a yearlong project. So, I narrowed it down to analyzing the gendered nature of children’s publishing in the nineteenth century.

What was the focus of your main research question?

The focus of this second portion of my project was to identify the topics that show up in children’s works intended for boys or girls, and to discover whether these topics were statistically significant by gender. Several scholars had discussed that in the nineteenth century, girls and boys were often treated as different consumers by publishers, and I was interested in what publishers thought boys would want to read, as opposed to girls. In deciding which books were intended for boys or girls, I assumed (although it was supported by research on the time period) that the work’s protagonist could be used as a proxy for intended audience (a male main character, for example, meant the book was intended for boys). Because a work had to have a male or female protagonist, which some like anthologies would not, only 613 of the 1020 works in the dataset were used to answer this question.

What do you mean by “statistically significant”?

Basically, it means that the results of the topic modeling were not random, but meaningful data. Topic modeling is a group of algorithms (I used Latent Direchlet Allocation, or LDA) which identifies “topics," or groups of words that often occur together over a number of texts, or documents.

However, with longer works, like novels, segmentation—or breaking the work into smaller chunks—is necessary to avoid topics becoming too general. So, before being used to train an LDA model, works were broken into approximately 1,000-character “chunks” (roughly 2–3 paragraphs). The model was then trained on all of these chunks, agnostic of the works’ intended audience.

Of the 125 topics produced by this model, 112 topics were statistically significant by audience gender (or protagonist gender) using a Welch t-test. So, essentially, almost everything about these books (and what they were paying attention to) was gendered.

And what were your findings?

Overall, I discovered that nineteenth-century children’s literature was significantly gendered. It was especially interesting to see how the subgenres that literary scholars had discussed—the boys’ adventure story, for example—showed up prominently in the topics: Islands (Stranding), Boats (Stranding, Shipwreck) and Materials (Rudimentary Survival) were all topics more present in the boys’ stories. As a sidenote, the topic labels (e.g. Islands) were ones I assigned after viewing the topic visualizations. More generally, boys’ topics focused on the “away,” even on specific geographic locations. There was a term related to the Gold Rush, and another on Scotland. Girls’ stories, on the other hand, were typically centered in the domestic space, focusing on family and home.

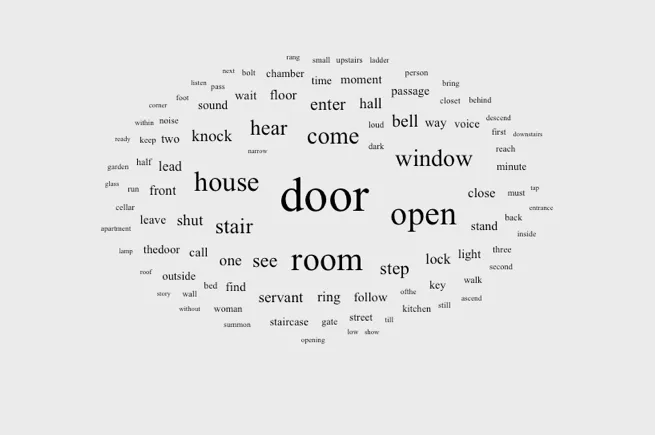

To better explore these nuances, my thesis included smaller case studies focused on related topics. My favorite case study was the domesticity case study. By looking at the topic models, I discovered that the topic with the third-smallest mean difference (essentially found most equally in both boys’ and girls’ books), or one of the least-gendered topics, across the board was the Entry into Space (Domestic) topic, which is shown below. So, even though boys’ literature might be preoccupied with the absence of the domestic, or the “away,” its characters are still entering these domestic spaces. However, while the “girls’ topics” indicate significant time spent in the domestic space, the boys’ topics indicate very little time spent in the “home” of children’s literature. Among other things, this raises a lot of interesting follow-up questions about boys’ estrangement from the home in nineteenth-century literature and society.

Word cloud of Topic 15: Entry into Space (Domestic). Beyond the inclusion of words (servant, bed, kitchen, cellar, garden) that implied that the space being entered was a house, several words in this cluster also appeared in other clusters more clearly discussing the domestic space.

What led you to this research topic?

Originally, I was hoping to accomplish a computational literary analysis project more ambitious than my previous research. My junior paper focused on gender in the work of early female British novelists but had a limited scope—the dataset included seven authors and 35 novels. For my senior thesis, I wanted to attempt a higher-scale literary analysis that could speak more comprehensively to its time period.

However, especially as a computer science major, I wanted to ensure I had the requisite genre knowledge for the project. My choice of children’s literature was partially because I had that minimum domain knowledge. I asked Karthik Narasimhan in the Computer Science department to be my primary advisor and William Gleason in the English department to be my secondary advisor. I had taken Children’s Literature (ENG 385) with Professor Gleason, which was one of my favorite courses at Princeton. Further, choosing children’s literature ensured there was enough material from my dataset because the genre is defined by audience, rather than style or form. Therefore, there were a fairly large number of works available for analysis. These reasons were the initial seeds that pushed me to research children’s literature and consider it as the basis of my project.

After looking into it, I realized how much this project could speak not just to literary history, but to cultural values. In my opinion, this tends to be a strength of the digital humanities generally, but especially children’s literature—after all, what we teach children says a lot about ourselves. Further, the nineteenth century is a fascinating time in children’s literature, and being able to use the catalogue of the Cotsen Children’s Library helped me feel more confident in my dataset as a first-time curator.

Even though the choice of children’s literature was because it met the project’s requirements, the time I’ve spent reading children’s literature scholarship and immersing myself in the genre this year definitely spurred a scholarly interest that will follow me into future studies. I still have so many questions I’d love to answer regarding the genre.

Tell me more about your interests in both computer science and digital humanities.

My love of English goes back to childhood. I know it’s common to say this at Princeton, but reading really was my personality as a child! Still, re-reading children’s literature as an adult has been shockingly rewarding: many of my favorite childhood books still hold up, and, of course, take on new meaning for me now that I’m older.

As for computer science, I’ve known that I wanted to major in computer science since my freshman year of high school. However, this meant putting English on the backburner since computer science requirements consumed much of my schedule. However, I still wanted to take English classes. In my sophomore year, I took Claudia Johnson’s class on Jane Austen and loved it, which really spurred me to continue to pursue the subject in English.

There is no certificate in English, so there were no formal requirements for the classes I took. Accordingly, I got to take what I liked. The six classes I did take within the department are definitely overrepresented on my list of favorite college classes. The English Department has been great to me—even without being a member of the department, it was always so easy to reach out to professors for help, including with my research. Ultimately, my interest in English really goes back to my love for stories and storytelling: I also was a member of the Nassau Literary Review for my four years at Princeton, where I contributed as a prose editor.

My interest in computer science really began with my love for problem-solving. I’d always enjoyed the qualitative side of STEM, and its rigorous way of approaching open questions— I love proofs. However, I’d also felt more creatively free with how the humanities ask and answer questions. In some ways, computer science feels like where the two meet—it relies on a quantitative infrastructure, but there is no one way to solve a problem, allowing more creativity and collaboration.

Combining the two was largely motivated by Princeton’s research requirements. When I was considering what direction my research would take, I spoke to Professor Kernighan in the CS department. He suggested I look into doing a computational project about Jane Austen, and into working with Professor Fellbaum, a professor of both Computer Science and Linguistics. Still, it wasn’t until I started talking with Professor Gleason about my senior thesis that I realized how much of the digital humanities I had not yet even encountered. My senior thesis really helped me connect my previous research to the discipline as a whole.

You participated in Princeton Research Day this year. What was your experience like?

My roommate (Sophia Richter—she ended up winning an Orange and Black Award) was doing Princeton Research Day, and she encouraged me to join. Especially as someone considering further graduate study, it was a great opportunity to consider how to make my research accessible. Such a salient concern with digital humanities is how to get the public involved, and increase accessibility to the humanities. While I had always been passionate about that, Princeton Research Day was a great way to practice that, not just contemplate it. Participating allowed me to think more critically about how to share the project, even with those who may have never heard of the digital humanities.

What are your post-Princeton plans?

In August, I will be starting as a software engineer at MongoDB, a tech company that provides an Atlas, a database-as-a-service (essentially simplifies data storage and access for clients). I interned with them last summer, and really loved the experience. I’m looking forward to working in the tech world full-time.

I was privileged to be accepted to a digital humanities Master’s with a faculty I was excited to work with. However, I decided to decline both because I wanted to continue working for my company and hoped to take some time off from academia. In the long-term, I am definitely interested in further exploring the intersections of tech and culture in academia or industry (or both!)

Congratulations, AnneMarie! You can read more about the CDH Senior Thesis Prize and past winners’ projects here.